So the other day I’m doing a code review in an enterprise application. The goal was to switch the data storage from SharePoint Online Lists to Azure SQL database tables. “Easy,” I thought. “It’s just a change in the Data Access Layer (DAL)”.

Long story short, I started reviewing the source code and… wasn’t amused. This was (a small sample of) the problem:

public class AdminService{ public AdminService(ILogger<AdminService> logger, ISharePointService sharePointService, IConfiguration configuration) { // initialization code } public async Task<Metadata> AddEmployeeDirectoryItem(PnPContext adminContext, PersonCreated personCreated) { // Add Employee Directory stuff } // etc etc} I mean, dear programmer, look. You want to add a directory related to an employee. I get it. But why is the PnPContext sitting there in the method signature like an uninvited guest at a wedding?

This is what we call a “Leaky Abstraction.” Your Data Access Layer (DAL) is leaking its internal stuff all over your business logic. Depending on the case, today it’s Sharepoint, tomorrow it’s SQL Server, and the day after it’s a carrier pigeon. If your business logic knows in what kind of medium your data is stored in, you’re in for a world of hurt.

The Problem: When your DAL tells too much

The core issue is coupling. When you pass an SqlConnection, an SqlDataReader, or a SharePoint PnPContext directly into your business services, you are essentially tattooing your data vendor onto your forehead.

If you leak these details:

- You can’t switch providers: Moving from SQL to SharePoint to Oracle to clay tablets becomes a “rewrite everything” project instead of a “change one class” task.

- Testing is a nightmare: You can’t unit test your business logic without a Sharepoint, SQL Server etc. running, because your methods demand a real connection.

- Code smell: Your business logic should care about what is being saved, not how the connection string is formatted.

The “Wrong” Way: The Leaky Bucket

Take a look at this example. It’s the kind of code that works fine during development, works fine in UAT, but makes you want to retire when requirements change.

// Somewhere in the Business Logic Layerpublic void ProcessInvoice(int invoiceId, string connectionString){ using (SqlConnection conn = new SqlConnection(connectionString)) { conn.Open(); // Why is my Business Logic managing SQL connections?! var cmd = new SqlCommand("SELECT * FROM Invoices WHERE Id = @id", conn); cmd.Parameters.AddWithValue("@id", invoiceId); // ... process logic ... }}Did you notice? The business logic is doing the heavy lifting of database management. If the boss says “We’re moving to an OData API,” you have to touch every single file in your project.

The Solution: The Repository Pattern

So how do you do this correctly?

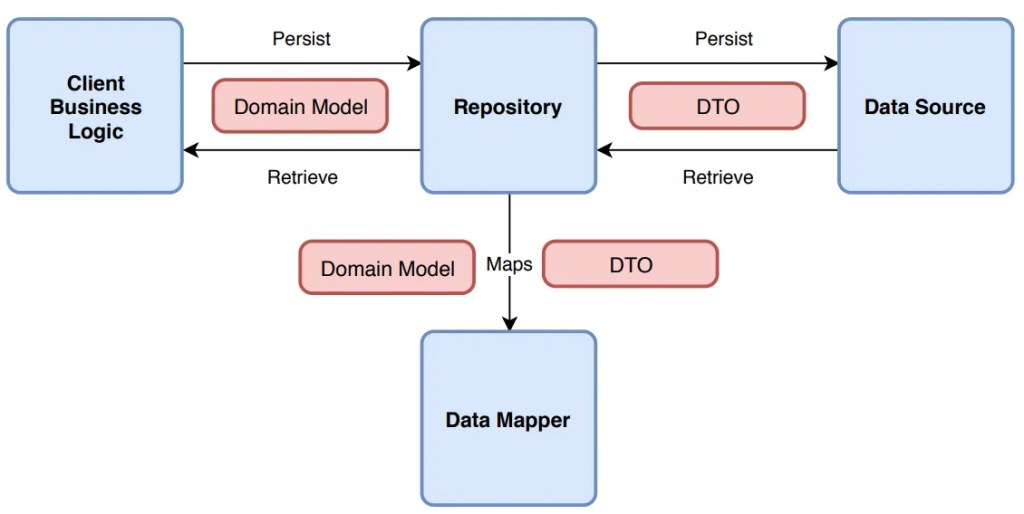

First of all, it’s a good idea not to reinvent the wheel. You can use the Repository Pattern. Think of a Repository as a mediator between the domain and the data mapping layers. It acts like an in-memory collection of domain objects.

Your business logic should talk to an Interface, and that interface should speak the language of your business (Invoices, Customers, Files), not the language of your storage (Tables, Blobs, Transactions).

The Refactored Way: Clean and Dry

Let’s fix that mess. First, we define what we want to do, without mentioning the data storage medium. Here’s an example of an invoice processor:

1. Clean business objects

public class Invoice{ public int Id { get; set; } public string CustomerName { get; set; } public decimal Amount { get; set; } public DateTime IssueDate { get; set; } public List<InvoiceItem> Items { get; set; } = new List<InvoiceItem>(); // You can add business logic here... public void ApplyDiscount(decimal percentage) { Amount -= Amount * (percentage / 100); } // ...but NEVER data access logic!}public class InvoiceItem{ public string Description { get; set; } public decimal Price { get; set; }}2. Repository Interface

public interface IInvoiceRepository{ Invoice GetById(int id); void Save(Invoice invoice);}Notice how the interface uses only basic types (such as int, string etc) or our clean business objects. It should NEVER use data store-specific types, such as DataRow.

3. The Business Logic (the right way)

Now, the business logic is blissfully ignorant. It’s like a person ordering a pizza who doesn’t care if the oven is electric or wood-fired.

public class InvoiceService{ private readonly IInvoiceRepository _repo; public InvoiceService(IInvoiceRepository repo) { _repo = repo; // Dependency Injection! } public void ProcessInvoice(int invoiceId) { var invoice = _repo.GetById(invoiceId); // Do actual business work here... _repo.Save(invoice); }}3. Data layer implementation

Now, you can have a SqlInvoiceRepository for today, and a SharePointInvoiceRepository for tomorrow. The rest of your app won’t even notice the difference. All they need is to implement IInvoiceRepository.

Final Thoughts

It’s tempting to just “pass the connection” because it’s faster. It’s easy to forget that code lives longer than infrastructure.

But in any case, be careful to consider your future self (not to mention others that might maintain your code). Is your software supposed to grow? A good place to start is decoupling.

Whatever you do, PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE DON’T LEAK YOUR DAL DETAILS.